Listening to our practice

Dylan Chevalier

Judo Club Perros-Guirec

Exam date: 1st of June 2024

Supervising Teachers: Philippe Chanclou & Yann Ao’Drenn

Technical Commission referents teachers: Michel Luguern & Jean-Marc Douguet

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is the result of work carried out with the participation of several people.

First of all, I’d like to thank Philippe Chanclou and Yann Ao’Drenn for being my supervising teachers.

I’d also like to thank my teachers Michel Luguern and Jean-Marc Douguet, both members of the FIAJ Technical Commission, for monitoring my work. This work was carried out at the same time as that of Cédric Delmotte, so I’d also like to thank him, as we exchanged a great deal on our respective projects. I’d also like to take this opportunity to thank the Perros-Guirec practitioners, and in particular Gilda Le Buhé and Laurence Le Gall, both of whom work in the music and singing world, for helping me to learn some fascinating things about sound.

I’d also like to thank the students at the Saint-Méen-le-Grand school, where I started out, and the school in Angers, where I stayed for two years to study. I’d like to thank all the students for their studies. Above all, thanks to the FIAJ Technical Commission for taking the time to read my work and allowing me to discuss my teaching subject.

Finally, I’d like to thank my parents for depriving me of television for 10 days in May 2013 and thus allowing me to discover Junomichi.

1. Introduction

To understand my choice of subject for my professorship, I think it’s important to tell my story, i.e. my encounter with Junomichi and the journey I’ve made to date.

It all began in May 2013, when I was in secondary school. For the first time, the school organized a week called ”10 days without screens”, and that’s when my parents had the good idea to follow this initiative. To avoid any temptation, the school, with the help of associations in Saint-Méen-le-Grand, organized activities every evening during this period. It was at this time that I discovered the Saint-Méen-le-Grand Junomichi school and its members, where I did a trial session. So, what convinced me? The answer is

De Ashi Barai. During a demonstration, the teacher, Yann Ao’Drenn, projected on De Ashi Barai, adding the words: ”I’ve just projected without using force”. This sentence may seem rather utopian, given that we live in a society that would have us believe the opposite, but it sent an electric shock through me. Unlike Mr. Igor Correa, it wasn’t the screens that made me discover Judo.

So it was in September 2013 that I started Junomichi in Saint-Méen-le-Grand. I stayed there for 4 years until I had the opportunity to leave for my higher studies in Angers. Although I had taken part in a number of internships, it was an opportunity for me to see what was being done in other schools. During my time in Angers, I was able to attend various Junomichi classes in the surrounding area. In the end, and still for my studies, I ended up in Perros-Guirec, where I still practice. Through my various school visits, I’ve been able to soak up different teachings to enrich my practice and, as best I could, develop ”my” Junomichi.

As you may have understood, I’ve always practised Junomichi. But that hasn’t stopped me from going to schools where sport judo is taught. This was the case during my stays in Canterbury, England and Riga, Latvia, where I was called upon several times to teach in schools at the request of those leading the sessions.

This story brings us to the subject I chose for my professorship: sound in Junomichi. My initial approach was to link speech with Junomichi. The link you have with your partner when you practice, and more specifically during Randoris or Shiais, can be seen as a form of communication, hence the idea of ”speech”. However, initial feedback made me realize that my approach was too ”psychomotor”. So, my subject evolved towards sound.

The practice of Junomichi is sound-based, and unfortunately, we don’t pay much attention to the sounds we produce. This manuscript is an opportunity for me to share and, above all, exchange views on a subject close to my heart. It’s also a way of finding more autonomy in my practice and, one day, perhaps opening a school myself or taking part in teaching.

2. Sound family. Words in Junomichi

2.1 Body sound

2.1.1 Breathing

The first sound I’d like to mention is the breath. Breathing is essential, as poor breathing will create tension in the practitioner’s body and be transmitted to his or her partner (or the group). Paying attention to the sound we produce can be a gateway to becoming aware of our own breathing or that of our partner. In my opinion, breathing is a good indicator of relaxation.

Firstly, the breath must produce a continuous rhythm of sound. A discontinuous sound is characterized by stops, and in Junomichi, we seek a flow and the calming down in all our movements, and this also involves breathing. To achieve this, breath must pass through the nose, not the mouth.

Mouth breathing leads to an imbalance between inhalation and exhalation. This phenomenon can easily occur during Randoris and/or Shiais, as the rate of practice increases.

Secondly, once the breath is continuous and relaxed, you need to pay attention to the way it is done. Like any movement, it is produced by the belly, and more precisely by ²the diaphragm.

2.1.2 Movements (Ayumi Ashi)

Do we pay enough attention to our movements on the tatamis? Indeed, when we walk, we naturally create an imbalance by putting our body forward to move a leg further away and so on. If we pay close attention to our movements, we can sometimes hear a discontinuous, jerky sound caused by pauses in our movements. This can be corrected by stepping with more amplitude and gliding, while maintaining a good attitude through Shizentai [7]. Good movement is therefore achieved with smooth steps, mobilizing the whole body. A slight sound of friction is produced. The sound can be represented as light strokes made with a pencil. Between each stroke, there is a silence, as in the movement. These moments of silence are very interesting, as they set the rhythm like a metronome.

I believe that the accuracy of movement can be demonstrated in the Koshiki No Kata. Practitioners are symbolically dressed in traditional Japanese armor. As a result, the movement is set in motion by the forward movement and the weight of the armor, so the movement can only be continuous. The movement you make alone must be exactly the same as with a partner: no change of attitude. When the movement is well executed, you should hear a single movement at all times [6]. Sometimes, the movement is neglected because the idea of projection is in the mind.

2.1.3 Ukemi

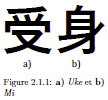

After the sound of mobility comes the sound of Ukemi, i.e.Mae Ukemi, Yoko Ukemi and Ushiro Ukemi. Before goingany further, I’d like to clarify the meaning of the termUkemi. It’s made up of two kanji (see figure opposite),”uke” and ”mi”. Uke means to receive. It is broken down with the kanji of the hands, as if receiving water to createa ”bowl”. The kanji Mi refers to the body in general, butits etymology quickly refers to the pregnant woman. Thetwo together mean to receive one’s body, with the idea of

protecting it like that of a pregnant woman.

From Kanō Jigorō: ”Before entering the Randori exercise, you need to know what we call Ukemi. Ukemi are a way of falling pleasantly without injury or pain, whether you fall by yourself or are thrown by someone else. With this, you can fall forwards, backwards, to the right and to the left, and sometimes even roll. If you can’t do this exercise freely, you can’t do Randori properly.” [3, 9].

The predominant sound of Ukemi is that of striking the ground. This sound is produced by an action of the body that will release the energy moving away from (or out of) the body through the striking hand. Ukemi is the action of putting oneself forward to enable continuous attacking, to regain control over Tori’s reaction to Uke’s attack.

For the Ukemi to be well done, it must above all be in Tori’s action, relaxed with good breathing and bove all followed by the strike of the hand with a relaxed arm. The sound of the strike is a marker in Junomichi. It tells us whether Uke has done his Ukemi and Tori has done his projection. This strike is also the sound of the body on the tatamis,helping to restore consciousness when moving from the standing position to the ground (loss of balance). This sound, which escapes from the body, releases energy that would be destructive if it remained within us.

2.1.4 Tapping when partner is controlled

In the practice of Ne Waza, there are Shime Waza and Kansetsu Waza, which respectively control the blood flow to the neck and control the joints. When the partner is well controlled, he/she taps twice, ideally on the partner, to let him/her know that the control is good and that he/she should go no further. The resulting sound is dry and clearly audible to the partner, and possibly to the observing Joseki. If this sound is hesitant / timid, injury may be caused.

2.1.5 Kiai

Kiai is a concept found in many Japanese martial arts, including Judo. The term ”kiai” can be broken down into two parts: ”ki” meaning energy, and ”ai” meaning encounter. In [5], the Kiai is defined as the following way: Kiai – freeing the breath – energy / meeting Intimately linked to the attack, the Kiai is the powerful, sonorous breath produced by the Junomichika during a decisive action. Performed in the time of an exhalation, the Kiai accompanies the work of unifying the body and prolongs it, transmitting fluidity and

power. The Kiai is the expression of the Hara.

When Kiai is emitted from the Hara, the process is the same as that used by a singer, who emits a powerful, controlled sound from the belly that requires no effort. The sound produced by the Kiai must represent the energy controlled when performing Atemis. A Kiai that is too weak is an insincere Atemi; conversely, a Kiai that is too strong is an uncontrolled Atemi [1].

Now that we’ve covered the sounds made by the body, let’s turn to the sounds in the spoken language of practitioners.

2.2 Sound in the language spoken by practitioners

This part refers to the language we use on the tatamis during our practice. The first question is why do we need to talk on the tatami? When I say ”talk”, I don’t mean chitchat, i.e. any subject not related to the practice of Junomichi. The first natural answer is that it helps to express an idea and make it easier to understand. However, these words must not encroach upon our practice, because firstly, understanding is unique to each individual and secondly, practice is done through sensations. I think this is necessary, because if a teacher didn’t give any explanations, there would be a lot more misinterpretations.

What’s more, using a language that is familiar to practitioners allows us to refer to a form. The problem is that forms expressed in Japanese can be translated in archaic ways, changing the idea of the form. For example, in [5], Hane Goshi is translated as ”leaping hip” (hanche qui bondit in French), but if you look elsewhere, you may come across translations such as ”impacted hip”. This second translation is no longer in line with the Junomichi principle of non-opposition. Japanese words are very important, and their use should be encouraged.

The meaning in the spoken language of practitioners is perhaps the most complicated to manage as a teacher. Words have to reflect the sensations you’re trying to convey.

Depending on the teacher and the time, words and formulations evolve. For example, in [4], Igor Correa says: ”The Kake is the push with the left leg, because that’s the one that pushes it into the mat”(Le Kake, c’est la poussée de la jambe gauche, parce que c’est celle qui permet de l’enfoncer dans le tapis, in French). Today, I think this sentence would be said differently, since there has been an evolution in conception. The words change over time, only the sensations remain the same.

The difference between French, English and Japanese is the richness of the Japanese language. From what I understand, Japanese has a language with more subtle words than French. In Junomichi, l’origine du judo (French Junomichi book) [5], Igor Correa refers to French as a poor language. The question is: should the entire terminology of Junomichi be translated? From my point of view, I don’t think it’s necessary, and although it may not seem instinctive, it’s preferable to use Japanese language in order to avoid misinterpretations such as translating Ukemi as ”breakfall” in English.

The Junomichi seminars in Scotland made me realize that practicing with a partner who doesn’t speak the same language helps in the understanding of the importance of the choice of words, and sometimes to limit speech to make more room for sensations.

2.3 Sound in the Japanese language

The sound in the Japanese language embodies all the principles of Junomichi. In this section, the different sounds have been classified into 3 parts. These sounds reflect Junomichi terminology, or simply ”Junomichi no kotoba” [5].

2.3.1 Sound of conscience and respect

Respect is an important cultural norm in Japan, and one that’s reflected in our practice on the tatami. Respect can be seen as a decision to work with a maximum of commitment.

This respect is above all symbolized by a collective bow at the beginning and end of practice. This moment should not be neglected, as it represents one of the values of our practice, but above all it enables us to go together into the practice. The bow is performed together by the expression of two phrases: ”Shomen Ni Rei” and ”Sensei Ni Rei”. The term ”Shomen” can be used to describe the origin or source of a particular phenomenon or entity. It indicates the fundamental aspect of something. In this way, ”Shomen Ni Rei” will indicate to practitioners that they are going to greet the people behind our practice. As for ”Sensei Ni Rei”, this phrase will indicate to practitioners that they are greeting the teacher or simply the person who will be leading the class.

The way these phrases are pronounced must be loud and clear, so that everyone can hear. Behind this bowing lies a representation of Kime, i.e. the decision to practice together.

At this point, you can also introduce the bow in the body sounds section presented above. In complete silence, we all come together, in order of title, to perform a sliding step backwards before going into Seïza. Before the two phrases are uttered, practitioners turn to either the Shomen or the Sensei. All practitioners can be heard sliding their hands across their judogis and the tatamis. The bow ends with the passage from Seïza to Shizentaï.

The bow is something we do together. Just as when you practice with a partner, if you’re not with him or her, you can’t do anything. But here, it’s the group that has to be together to enable this richness of practicing together and sharing this story.

2.3.2 Symbolic sound

2.3.2.1 Titles

As the Junomichika progresses through the history of Junomichi, he/she will evolve in his way of being and his/her practice. This evolution is marked by what we call titles, which are unique to each individual. When you start out, you’re what we call 6th Kyû, which corresponds to the first level of value for beginners, and then you move on to what we call Dans, which attests to longevity in practice. In the past, when you earned a black belt, you were said to have earned the title of first Dan. Today, although we still

hear the term ”dan”, each title has a name associated with it, which has a significant value and can be associated with a categorization in practice.

2.3.2.2 Katas

The foundations of Junomichi are illustrated by Katas. Katas are codified forms that illustrate a pillar of our practice.

”For Kano Jigoro, judo kata should not be an inventory: indeed, the techniques contained in all Kata represent only a tiny percentage of Judo techniques. Instead, each Kata explores an essential principle of the method, or an area of it.” [3].

In a way, we could have imagined calling the Nage No Kata the first Kata, the Katame No Kata the second Kata, and so on. However, the names/sounds assigned to them serve to accentuate their importance. For example, if we take the Kime No Kata, this is the Kata that shows the decision in Junomichi.

2.3.2.3 Judge (Shinpan’in)

Among the symbolic sounds is that of the Shinpan’in, i.e. the judge during Shiai or Randori. The Shiai is a meeting between three Junomichikas, i.e. a judge and two participants. Two practitioners come to take the Kumi Kata with the aim of achieving an Ippon. Already, at this level, we can mention the different sounds mentioned above, that of breathing, movement, taking the Kumi Kata and projection. The third practitioner, the judge, is also part of the Shiai.

The three practitioners begin by greeting each other when the judge calls ”rei”. Once this has been done, the Shiai begins at the ”hajime” signal. In the case of a projection, the aim is not to rush to give a result, but to decide whether to announce an ”ippon”, ”waza ari”, ”osae komi”, ”sonomama” or ”toketa”. The Shiai ends with the practitioner who has achieved Ippon or Waza Ari announcing ”ippon gachi” or ”waza ari gachi” respectively. It may turn out that none of them managed to make an Ippon or a Waza

Ari, so the judge calls out ”hiki wake”. In the end, the three practitioners bow to each other before leaving the relationship that had been established between them.

How a Shiai evolves depends in part on the judge’s attitude, i.e. how he/she expresses himself. For example, a ”hajime” with little voice may reflect a certain amount of doubt about the decisions to be made, and above all a lack of decisiveness.

2.3.3 Descriptive sounds

After the symbolic sounds come what I call the descriptive sounds. In these sounds, I’ve included the Junomichi types of control and exercises that make up our practice.

2.3.3.1 Types of control

Forms of projection are merely a reflection of Junomichi practice. On the whole, we have a wealth of projections listed in what we call Ne Waza, techniques performed on the ground, and Nage Waza, throwing techniques;

The name/sound of the projection is important, as it refers to an idea, a form. Sometimes, you can find French/English translations of certain movements. The problem is that they refer to mechanical actions that lead to opposition. The question is, how can we explain a movement without translating it into an approximation in French or English?

This brings us back to part 2.2 on the sound in the language spoken by practitioners.

2.3.3.2 Exercices

In Junomichi, there are several exercises, and although they are performed differently, they all have the same objective: to achieve Ippon according to the five principles of No opposition, Decision, Self-control, Hara mobility and Encompassing. These are what we might call the seven fundamental exercises: Kata, Uchi Komi, Nage Komi, Yaku Soku Geiko, Kakari Geiko, Randori and Shiai.

Each of these exercises represents a very specific way of practicing Junomichi. Some of these exercises might suggest that you need to be in a certain physical condition to be able to do them, i.e. have no body problems/ restrictions. From my point of view, I believe that all these exercises can be practiced with all practitioners, whatever their physical condition (as long as they can stand upright). The point to watch out for is attitude. If the partner has a body problem/ restriction, this will enable them to become aware of the points of tension they may have and adapt their work. When the partner has a body problem, it can happen that the sounds resulting from the practice can be different. From time to time, I practice with people who have hand problems. So, when they are thrown, the sound emanating from the strike during Ukemi may be non-existent. Both as Tori and Uke, this disrupts the practice.

Sound through practice

3.1 Bow (Rei)

Throughout the study, practitioners will greet each other, starting with the collective bowing at the beginning and end. The most important thing to remember is to bow together, so that only one sound is heard (e.g. hands on the tatamis, Judogi sliding when the body bends), and so that we can link up in our history.

When a bow is made between two practitioners, you can hear them thank each other in person. I find this very interesting, as it helps us remember why we are bowing each other.

3.2 Ne Waza

In Ne Waza, when we pay attention to sounds, we can distinguish several that are also found in Nage Waza. The first thing I’d like to mention is breathing. Breathing is essential, since poor breathing creates tension and therefore opposition between you and your partner. Sound can be a gateway to awareness of one’s own breathing and that of one’s partner. Breathing is the first natural means of learning to relax. All movement is the consequence of good breathing.

Exercise:

To work on this aspect, i.e. the sound of breathing, I suggest lying on your back to become aware of the way you breathe. It’s important to disregard other practitioners as well as outside noises in order to concentrate on oneself.

When practicing with a partner, it’s important to maintain the same attitude as when practicing alone, both as Tori and Uke. Other sounds appear when taking back the control with a partner. There’s the sound of the Judogi rubbing against the tatami, the partner’s Judogi, and also the sound of effort. Attention to the sound of breathing can also accompany partners during this practice, even if speaking can accompany awareness of a sound or the progress of the practice.

Exercise:

In order to become aware of the different sounds produced with your partner, you can simply take back the control. At this stage, we can already ask ourselves about the quality of the sounds I produce alone and with my partner.

A sound often heard with beginners, i.e. Kyus, is that of falling during Ukemi. When Tori is about to take control of Uke, you can hear the sound of a body falling backwards onto the ground. This problem is often due to poor Ukemi and Uke’s inactivity. Attention must therefore be focused on the Ukemi.

Exercise:

To work on it, I like to use the following representation, which may have the disadvantage of a somewhat mechanical perception, but I think it helps you find your way to Ukemi. So, from the Seïza, we’ll raise one knee and form a circle with the arms and with the hand on the raised knee side slightly advanced and pointing inwards. At this stage, we can imagine that we have a rigid circle and that we’re going to roll on this circle by coming to put the knee, then the associated hand followed by the elbow, the shoulder blades, the elbow of the other arm and the hand which comes to release the energy of the body. When the Ukemi action takes place, the practitioner must ask himself and be aware about the sound of his breathing and especially the sound of the ”roll”.

Whether you practise Ukemi alone or with a partner, you’ll find the same concept, which is to practice Ukemi from the front. Ukemi can be seen as a gateway to Nage Waza, and to achieve this, it is first practiced on the ground before standing up.

Exercise:

To work on the continuity of Tori’s control, we can think of it as the study of Go No Sen No Kata, i.e. on Kuzure Geza Gatame, Uke will take control a first time to feel the direction and then a second time while controlling to become aware of the sound he produces. Do practitioners make continuous, synchronous sounds?

Earlier, we focused on a few sounds when practicing Ne Waza. We mentioned the sounds of breathing, of Uke’s and Tori’s attitude. The sounds of the body enable us to judge the quality of our projections during the various Ne Waza exercises, and more particularly during Randori, which often induces behaviors that are detrimental to our efficiency.

3.3 Nage Waza

Nage Waza is complementary to Ne Waza, meaning that the sounds are very similar and sometimes even identical. The first sound we’ll find identical to Ne Waza is that of breathing. In my opinion, this is all the more important as movements are made with greater amplitude, hence the importance of controlling breathing.

Exercise:

Let’s start by taking a moment to observe our breathing when we’re standing. Is my nose breathing with my belly? Is it continuous? Does it allow relaxation?

The sound that follows is that of mobility, i.e. movement. In movement, as in breathing, we must look for continuity of sound. To achieve this, we need to pay attention to our attitude: feet parallel, hip-width apart, limbs relaxed, mind at peace [7]. Once this attitude has been adopted, we can look for a flow in our movements through sound. The sound of the wind caressing the sand is a good example. The sound of movement can be compared to a pencil drawing lines on a sheet of paper.

Exercise:

At first, it’s a good idea to do this work alone, then with a partner. Both should ask themselves whether they produce the same sound when moving alone. As they move, one of them can close his or her eyes to feel the directions proposed by the partner, and pay attention to the sound they make.

It was mentioned earlier that our practice is also marked by the absence of sound. For example, in our movements, it gives a rhythm. This will reflect the energy used by the two practitioners, and sometimes, who is in control. Now, how can we avoid dissonance in the rhythm of our movements? To do so, we must first accept the directions proposed by our partner and then extend the given trajectory.

Exercise:

Same exercise as above, except that this time the focus is on the rhythm between the two practitioners. The idea is to evolve this exercise into Kakari Geko. This Junomichi exercise is very interesting, as it enables us to become aware of the sounds we make when we try to maintain control of the projections our partner wishes to make.

After moving, I think the next logical step is Ukemi. I think Ukemi is one of the first gateways to adopting a relaxed attitude as a Uke through exhalation.

Exercise:

To work on this, it’s a good idea to start on the floor. The amplitude of the movement is shorter, enabling you to find the right movement. Once you’ve done the Ukemi from the ground, you need to stand up, as the aim of the Ukemi is to enable Uke to receive a projection. The resulting sound will provide information on its quality.

In all our actions, we can question the heaviness of sound, i.e. the power of the sounds we emit. In music, a high point refers to a moment when loudness, rhythmic emphasis or emotion reach a distinctive peak. In our practice, pitch remains largely the same throughout. During projections, the sounds may be longer or shorter between the moment the Kumi Kata is taken and the Ukemi.

Exercise:

In order to become aware of the length of the sounds we produce, we take a form of projection: Harai Goshi in different movements. Firstly, we watch as we do so in the form of Nage No Kata. This way, we can detail the sounds during the projection. Secondly, we’ll do it in a single step and thirdly directly. By reducing the time of the projection, we’re going to try to make the Ippon directly, as in Shiai, i.e. to become aware of the sound as soon as we take the Kumi Kata.

3.4 Katas

3.4.1 Kime No Kata

Of all the Katas, I think Kime No Kata is the one with the most sound. As it unfolds, you can hear a lot of sounds. As in most other Katas, there’s the sound of breathing, movement and projections/Ukemis. In this one, we find the sound of Uke through his Tanto/Chôto, Kiais and so on. The passage with weapons is often associated with a much quieter moment for those watching the Kata. There’s a relationship between the practice and the Dojo as a whole in terms of the associated noise (or silence). Here, the focus is on the sound of the Kiai produced by the Atemi, not on the way in which the Atemi is performed [1].

Exercise:

On the first movement of the first series (Idori), we repeat Ryo Te Dori, where we focus our attention on how we express the Kiai. Is the action/sound coming from my Hara?

3.4.2 Ju No Kata

Unlike Kime No Kata, I think Ju No Kata is perhaps the least sonorous, which can be explained by the fact that there is no projection. Throughout the Kata, there are sounds produced by Uke’s movements and strikes as he/she is controlled. Previously, in the manuscript, the sound produced was presented as a means of judging the quality of our practice. Here, in Ju No Kata, it is the absence of sound (up to Uke’s strike and excluding movements) that can be seen as a means of judging practice.

Exercise:

To work on this notion, we’re going to do Roy Te Dori (the third movement of the first series). This movement is very interesting as it represents the notion of Uke’s control without sound.

3.4.3 Go No Sen No Kata

In Go No Sen No Kata, the study often used is that of projection first, then Kaishi Waza second, for each of the 12 movements that make up the Kata. Whatever the Kata, the most sensitive point in my opinion is finding the right words to convey it to someone. The problem with words is that they can sometimes be misleading in relation to the body’s sensations. This raises the question of the importance of words. On Cédric Delmotte’s initiative, I’ve worked on Go No Sen No Kata by limiting the use of words, leaving more room for sensations. The following exercise allows you to limit the use of words, and concentrate on sensations.

Exercise:

This work can be done if one of the two practitioners knows the sequence of movements. We’ll call P1, the practitioner who knows the Kata, and P2, the practitioner who is new to Kata. Starting with the first movement, P1 will project P2 and P2 will project on the same movement. P2 wants to project on the same

movement and in P2’s action, P1 will perform Kaishi Waza and vice versa. This form of work can also be envisaged for Natnastu No Kata.

Conclusion

Sound is present throughout our practice. The different families of sound in Junomichi have already been mentioned. There are the sounds of the body: breathing, movements, Ukemi, Kiai, etc.; sounds in the practitioner’s language, i.e. the sounds/words used by the teacher to explain concepts and describe our practice; and the sounds in the Japanese language, which provides the most accurate meaning in terms of terminology used in Junomichi.

The sound is an indicator of the quality of our Ippon. However, it is not the only indicator, as we have other senses which are also there to judge. William Braillon’s work on the question of aesthetics in Junomichi practice is a case in point [2]. The presence of sound, as well as its absence, gives us an idea of our practice. Sound has always been present in our practice. There have been times when we’ve heard

sounds that reflect good or bad Ukemi, projection and so on. However, I’ve never studied Junomichi through sound. As a result of this work, we can ask ourselves whether sounds are the reflection of sensations.

REFERENCES

[1] Yann Ao’Drenn. Concentration de l’énergie, la conduire dans un écoulement pour aller au dela. Approche par l’étude des ATEMI dans le JU NO MICHI. Manuscrit de professorat. Fédération Internationale Autonome de Junomichi (FIAJ), 2017, p. 11.

[2] William Braillon. Question de l’esthétique dans le Junomichi. Manuscrit de professorat. Fédération Internationale Autonome de Junomichi (FIAJ), 2019.

[3] Yves Cadot. “Kanō Jigorō et l’élaboration du jūdō − Le choix de la faiblesse et ses conséquences”. PhD thesis. INALCO, Dec. 9, 2006. url: https://hal.science/ tel-01625664 (visited on 07/31/2023).

[4] Igor Correa. Explications de M. Correa. url: https : / / drive . google . com / file/d/1Q39qgEBHcWvyJDGicESyhf8Eujjg- lNW/view?usp=sharing (visited on 05/12/2024).

[5] Igor Correa et al. Junomichi – L’origine du judo. 2010. isbn: 978-2-84617-273-8.

[6] Rudolf Di Stéfano. Ippon (Rudolf di Stefano) – Vidéo Dailymotion. Dailymotion. Running Time: 366. June 25, 2016. url: https://www.dailymotion.com/video/ x4icbz6 (visited on 05/06/2024).

[7] Gilda Le Buhé. Attitude Corporelle. Manuscrit de professorat. Fédération Internationale Autonome de Junomichi (FIAJ), 2023, p. 8.

[8] Lineage BJJ. 10th Dan Judoka Kyuzo Mifune – The Essence of Judo English Subtitled. July 12, 2016. url: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNInnePp- C8 (visited on 05/13/2024).

[9] Sanseidō 三省堂. “Jūdō kyōhon 『柔道教本上巻』(Manuel de jūdō, tome 1)”. In: KJTK-3 (1931), p. 312.